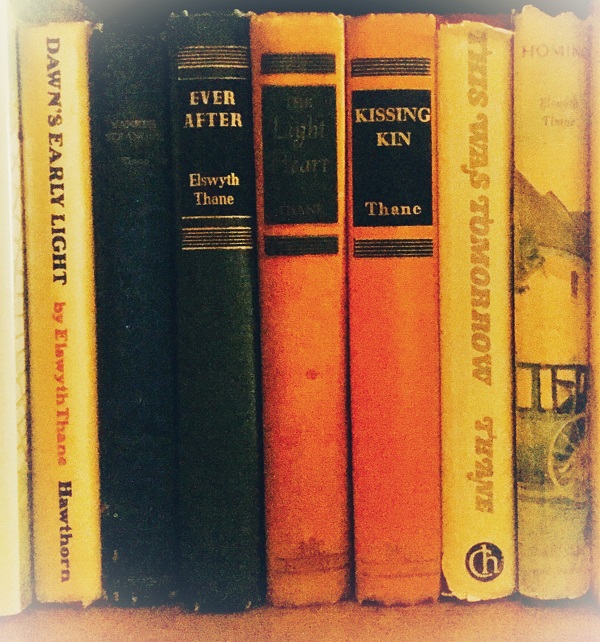

I’ve been reading Elswyth Thane’s Williamsburg series for most of my life, some of them more times than others. Recently I decided to read all seven of the books, and while some of my opinions hold, a few have changed dramatically.

How so? Let’s discuss. (Note: Spoilers don’t necessarily abound, but exist below.)

First up is Dawn’s Early Light, set in the years leading up to and during the American Revolution. Julian Day, a young Englishman, comes to Virginia and becomes a schoolteacher in Williamsburg, then the capital of the colony. He is taken in by a local family, makes lifelong friends, falls in and out of love, encounters a variety of historical figures, and finds himself unexpectedly caught up in the Patriot cause. The refined and rebellious St. John Sprague and his younger sister Dorothea, the arrogant and beautiful Regina Greensleeves, and the impoverished and steadfast Tibby Mawes all shape his experiences, and each has their own journeys and arcs. This has been one of my favorite novels since I first read it in elementary school, and I continue to love it–and it doesn’t hurt that late colonial America has always been one of my favorite eras.

Next is Yankee Stranger. Three generations later, the Day and Sprague families have intertwined and continue to live in Williamsburg (and Richmond). Eden, one of Tibby’s great-granddaughters, is swept off her feet by visiting New Jersey reporter Cabot Murray just as the Civil War breaks out. The suffering of soldiers and civilians alike is at the forefront for much of the story. I’ve usually found Eden to be a very passive heroine, but on this re-read I had a better appreciation for the tensions she experienced and felt that the risks she took made more sense for her character.

Ever After, third in the series, is the book in which Williamsburg begins to recede. The novel follows two storylines leading up to the Spanish-American War: Fitzhugh Sprague, who is supposed to join his father’s Williamsburg law practice but instead moves to New York City to become a reporter and composer, and Bracken Murray, who travels to England with his sister and their aunt and meets a young English girl. A very young English girl. Until this re-read, I would have said that Bracken was my favorite of Thane’s heroes. This time? Bracken disturbed me immensely. He meets Dinah Campion when she is 15, and methodically and intentionally grooms her. In contrast, the feckless and often frustrating Fitz takes a young (not quite as young) singer under his wing, but is focused on helping her escape a predator and become self-sufficient.

In The Light Heart, I found my new favorite heroine (of this series). I still love Tibby, but Phoebe Sprague–Fitz’s sister–really took me by surprise this time. She’s funny and smart and modern (she has her own apartment, and, if you read between the lines, lovers), she’s a novelist who is financially and socially independent, and she is a friend who goes above and beyond to help those she cares for. I don’t agree with all of her decisions, but Thane makes those decisions easy to understand and sympathize with.

But then. Then there’s Kissing Kin, set during and after World War I. This has always been my least favorite book in the series, and its chief protagonist, Richmond-born Camilla Scott, my least favorite heroine. For the life of me, I do not understand Camilla at all. She has an oddly strong bond with her twin brother Calvert (the only other Scott we meet, because apparently that side of their family doesn’t matter), in a way that reads more like . . . not quite obsession, but definitely fixation, and doesn’t seem to be reciprocated (although maybe that’s because I didn’t feel like Calvert was a fully realized character at any point). She falls instantly and irrevocably in love with a man who seems to have no personality at all. She neglects relationships and lets time pass unaware of the cost, and I suppose reflects people who had trouble finding their way after World War I–but in a manner that is very hard to sympathize with. Particularly coming on the heels of Phoebe, Camilla is a tremendous disappointment as a character. This was the book that was hardest to finish because I was just so frustrated with Camilla. She finds love in the end, but I couldn’t help feeling like Thane had put those two characters together because she couldn’t figure out what else to do with them.

The final two books, This Was Tomorrow and Homing, are set immediately before and during the early years of World War II. Because they follow the same characters during a fairly compressed time frame, they might almost have been a single novel. Williamsburg is now more of a refuge (at the end of Homing, one character is sent there from England for safety), and there’s an unsettling note of reincarnation and destiny that, because of the relative ages of the characters, takes one relationship back into disturbing territory. This time I was really struck by how juvenile the Spragues and Days and Campions in these two books seem in comparison to their counterparts in earlier novels, even though they tend to be a few years older.

Additionally, I now am much more aware of Thane’s sexism (flirtatious young women need to be dominated and controlled by strong men for their own good) and racism (her Black characters are stereotypes; one character and her daughter are unredeemable because they may have Indian as well as English heritage, and both women are shown to lack courage; and everyone is relieved to learn that no, that secondary character is not actually Native American). In Thane’s world, the only thing to be is White–and particularly English. The French are untrustworthy (except for in Dawn’s Early Light) and the Germans are without exception brutal.

On a less societally disappointing note, one of my dissatisfactions throughout the series is with character deaths.

- One character dies in between books, deciding at age 72 to try to break a horse that no one else could ride. While Thane does have some characters for whom this would make sense, to me it’s never felt like a decision that particular character would make.

- One major character must have died between books, but it’s never mentioned by any of the many, many surviving relatives.

- One character dies away from home on a business trip. Of course, this can happen, but somehow the tone of it doesn’t quite fit–there’s an odd callousness to the description, which I think is Thane’s inability to convey the shock of this fairly young character succumbing to the influenza pandemic (which is barely mentioned, and perhaps that is part of the problem).

- One character . . . well, I know he died, but he was such a nonentity in spite of his purported importance to other characters that every time I read the passage, I wind up feeling that his demise is more like a disapparation than a death. (Okay, this one is Kissing Kin‘s Calvert Scott.)

The end result is that I think Thane didn’t know how to write deaths, and pushed them to the side to avoid dealing with the challenge.

I still love the series, and I know I’ll read all of these books again (even Kissing Kin, I suspect), although I definitely read them differently now than I did a decade or two ago.